SSS’ Strategic Victory Against Terrorism

By Rekpene Bassey

In a rare moment of good news in Nigeria’s long war against extremism, the Department of State Services (DSS) has confirmed the arrest of Abubakar Abba, the elusive and feared leader of the Mahmuda terror group. Captured alive in a quiet but meticulously planned operation in Wawa, Niger State, Abba’s arrest was the culmination of weeks of human intelligence gathering, electronic surveillance, and delicate coordination with local communities. Not a single shot was fired.

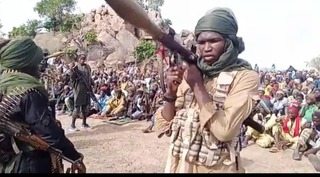

At 33, Abba is a study in the modern trajectory of West African militancy. Born in Daura, Katsina State, he entered jihadist circles as a teenager, selling tapes of radical clerics, including Boko Haram’s founder Mohammed Yusuf. From a peddler of propaganda, he became a battlefield commander, earning his stripes in Boko Haram’s violent campaigns before splintering off to lead the Mahmuda faction. His rise illustrates a pattern seen across the Sahel: ideological indoctrination morphing into battlefield leadership, with survival hinging on adaptability to changing security pressures.

The Mahmuda group itself is no ragtag gang. Emerging in the mid-2010s after a leadership rift in Boko Haram, it carved out a niche as a hybrid insurgent-criminal network. Its fighters alternated between ideological attacks and purely economic kidnappings-for-ransom. Their operational footprint centered on the dense forests around Kainji National Park, a region notorious for harbouring militant camps, but their reach extended into rural Kwara and deep into Niger State. The terrain; rugged, remote, and dotted with unmonitored routes into Benin and Niger; offered perfect cover.

DSS officials say Mahmuda’s ties to regional terror franchises in Mali and the Niger Republic made the group especially dangerous. Intelligence suggests a two-way exchange: Mahmuda provided fighters and safehouses to Sahelian jihadists, and in return received weapons, explosives, and tactical training. This relationship mirrors the operational strategies of Islamic State affiliates in Africa - networked cells, cross-border mobility, and revenue diversification through smuggling and extortion.

One of the lesser-known elements of Mahmuda’s survival strategy was its recruitment pipeline. According to security sources, the group targeted disillusioned young men in remote farming communities, often those displaced by climate-induced agricultural collapse. Recruiters offered stipends, motorbikes, and a sense of belonging. For some, ideology came later; for others, it was the first lure. What made recruitment effective was its local tailoring; preachers couched militant rhetoric in the language of community grievances, from government neglect to corruption.

Funding was equally sophisticated. While ransoms from kidnappings remained the group’s primary income, it is believed that Mahmuda also tapped into illicit gold mining profits in Zamfara, as well as cattle rustling operations stretching into Burkina Faso. Money moved through informal hawala networks, blurring the lines between criminal proceeds and ideological financing. Tracing these flows required both financial forensics and human sources embedded in trading hubs across West Africa.

This is where the DSS operation truly distinguished itself. Sources close to the mission reveal that the breakthrough came not from satellite imagery or intercepted phone calls, but from a local informant; a former group member who defected after his family was targeted in an internal dispute. His intelligence placed Abba in a safehouse near Wawa, disguised as a merchant. From there, the DSS built a low-visibility surveillance cordon, moving operatives in civilian clothes and using unmarked vehicles to avoid tipping off the group.

The arrest itself was a masterclass in restraint. At dawn, DSS operatives surrounded the safehouse. Abba, perhaps sensing the net closing, surrendered without resistance. It was important to take him alive.

A dead man can’t tell you who his financiers are or where the weapons are buried.

Governor Mohammed Umaru Bago of Niger State, in his public remarks, praised the “quiet professionalism” of the DSS and credited President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s administration for its “unflinching commitment” to dismantling insurgent networks. For communities long trapped in the crosshairs of violence, such praise resonated; though tempered by the reality that one arrest, however significant, is not the end of the threat.

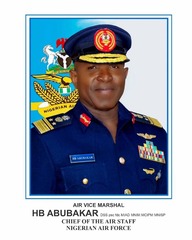

Under the leadership of Director-General Adeola Oluwatosin Ajayi, the DSS has leaned heavily into intelligence-led counterterrorism. Ajayi, a career intelligence officer with a reputation for precision and reform, has prioritized inter-agency collaboration and the use of indigenous knowledge in tracking high-value targets. The Wawa operation, originally his covert operations brain child, validates a doctrine that pairs modern surveillance with traditional community intelligence networks.

But as counterterrorism analysts often warn, leadership decapitation is a double-edged sword. In some cases, removing a leader fractures a group into smaller, more unpredictable cells. DSS strategists are aware of this risk. Follow-up operations should therefore be already underway to locate Mahmuda’s deputy commanders and secure weapons stockpiles before they can regroup or retaliate.

The arrest also plays into Nigeria’s regional security calculus. With Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso in varying states of political flux, and in some cases pivoting away from Western security partnerships, Nigeria cannot afford to allow its northwest to become the next ungoverned sanctuary for jihadist groups. The Wawa operation sends a signal not only to terrorists but to regional partners: Abuja is prepared to act decisively within its borders.

For President Tinubu, this victory comes at a politically advantageous moment. His administration has pledged to overhaul Nigeria’s security architecture, and delivering visible results strengthens his position both domestically and internationally. Yet, the public will judge the administration not on isolated wins but on whether such operations produce sustained security improvements in daily life.

In Wawa and surrounding communities, there is a cautious return to normalcy. Farmers are venturing back to their fields, and traders are reopening shops. But memories of kidnappings and raids linger. The locals have seen commanders come and go. What they now want is to live without fear, every day, not just after a big arrest.

Of course DSS officials share this understanding. They are quite aware that intelligence gathered from Abba’s interrogation will be used to map Mahmuda’s financial, logistical, and recruitment networks, with a view toward dismantling the infrastructure that allowed the group to operate for so long. This is not just about catching a man, it is about breaking the system that made him possible.

In the end, the Wawa operation may be remembered not just as the day the Mahmuda leader was caught, but as a case study in the evolving face of Nigeria’s counterterrorism: rooted in the ground truth of local informants, amplified by technology, and executed with surgical precision. Whether it marks the beginning of a lasting shift, or just another chapter in an ongoing war, will depend on what follows in the months ahead. But one thing is certain. The current Director General of the State Security Service came prepared. His management team and himself seem to know their onions.

Rekpene Bassey

Security Specialist, president of the African Council on Narcotics (ACON)