ECOWAS and the burden of misplaced blame in the Sahel’s AES

As insecurity deepens across the Sahel and military coups continue to reshape political power, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has increasingly become a convenient scapegoat. Officials and citizens alike have subjected the regional bloc to harsh criticism, sometimes justified, but more often driven by frustration and misdirected blame.

Much of the criticism levelled against ECOWAS reflects a tendency to ascribe to the organisation responsibilities it neither exclusively bears nor possesses the means to fully discharge. Like all intergovernmental bodies, ECOWAS derives its authority solely from the powers voluntarily transferred to it by its member states. Its capacity to act is limited by the political will, coherence and strength of those states. Where members undermine collective decisions or pursue contradictory policies, the organisation cannot be expected to deliver outcomes that exceed the tools placed at its disposal.

These elementary realities are often absent from the most popular critiques of ECOWAS. Strikingly, they are sometimes overlooked even by respected intellectuals, including seasoned journalists and political actors, whose analyses carry weight beyond the rhetoric of the Sahelian extremist online sphere.

This contradiction came into sharp focus following the recent ECOWAS summit held in Abuja from Dec. 14 to Dec. 15, 2025. In a widely circulated critique titled “When security serves as a cover for imperial tutelage,” Nigerien journalist and former minister Salou Gobi took aim at three key resolutions adopted by regional leaders: the reaffirmation of zero tolerance for coups, the activation of the ECOWAS Standby Force, and a more proactive crisis-prevention strategy.

Central to Gobi’s argument is the claim that ECOWAS has failed to denounce “constitutional coups” situations in which civilian leaders manipulate electoral processes, constitutions or parliaments to retain power with the same vigour as military takeovers. This argument, frequently echoed by supporters of Sahelian juntas, seeks to place military coups and constitutional manipulation on the same moral and political plane.

While such reasoning resonates with segments of the public, particularly younger citizens unfamiliar with prolonged military rule, its use by a seasoned political thinker raises deeper concerns. By equating these two fundamentally different forms of power seizure, critics risk trivialising the most violent and destabilising assault on democratic order: the military coup.

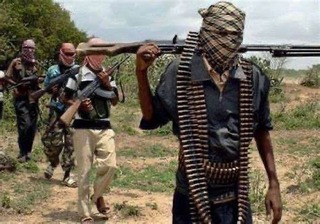

Military coups, by their nature, represent a radical rupture with popular sovereignty. Armed actors with no democratic mandate seize power by force, often suspending or abolishing constitutions, dissolving political parties, suppressing civil society and silencing the media. Constitutional coups, though equally condemnable in democratic terms, operate within a legal framework that, however distorted, preserves a minimum of institutional continuity and civic space.

The distinction is not theoretical. In countries such as Niger, which have experienced both phenomena, the contrast is stark. Military coups typically replace citizens with subjects, elevating armed force above law and turning power holders into unchecked sovereigns. The resulting authoritarianism leaves little room for dissent or reform.

It is for this reason, analysts argue, that ECOWAS places greater emphasis on opposing military takeovers. While neither form of power abuse is defensible, their implications are not equal. The consequences of military rule for civil liberties, economic stability and regional security are demonstrably more severe.

Critics are also quick to fault ECOWAS for security arrangements in the Sahel, including the presence of foreign forces and now-defunct mechanisms such as the G5 Sahel. Yet these architectures were neither conceived nor imposed by ECOWAS. They were the result of sovereign decisions by Sahelian leaders, often made outside the ECOWAS framework and, in some cases, with the apparent intention of sidelining the regional bloc.

Assigning responsibility for these choices to ECOWAS obscures the role played by national governments in shaping and sometimes weakening regional responses to terrorism and instability. It also feeds a narrative that elevates military “transitions” as expressions of sovereignty, despite limited evidence of improved security or governance outcomes.

Two years after the creation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), touted by some as a sovereign alternative to ECOWAS, the security situation in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger continues to deteriorate. Attacks have intensified, civilian casualties have mounted, and economic pressures have deepened. The facts, observers note, remain stubbornly resistant to ideological reinterpretation.

Even some of the most vocal critics of ECOWAS have acknowledged this reality. In a separate publication titled “Proclaimed sovereignty, sacrificed people: the great misunderstanding,” Gobi himself highlighted the gap between rhetorical sovereignty and lived experience a contradiction that underscores the limits of military-led governance.

Analysts argue that genuine sovereignty cannot be measured by slogans or institutional withdrawals alone. Rather, it is reflected in the dignity of citizens, access to justice, progressive economic autonomy and the preservation of fundamental freedoms. Without these, sovereignty risks becoming little more than an incantation, invoked to legitimise new forms of domination.

Ultimately, ECOWAS, like any regional organisation, can only reflect the collective will of its member states and peoples. Its transformation into a truly people-centred institution depends not on its denunciation, but on sustained civic engagement and political accountability within member countries.

That mobilisation, however, is increasingly constrained under military regimes, where public debate is curtailed and dissent suppressed. Ironically, this reality has been powerfully described by some of the same intellectuals who now defend “sovereign transitions.”