How ground pressure, air power are reshaping the war against banditry in Nigeria’s North-West

By Zagazola Makama

The opening days of 2026 have laid bare a defining reality of Nigeria’s North-West security landscape: the war against banditry is no longer episodic or localised, but a fluid, intelligence-driven contest unfolding simultaneously across multiple states, terrains and threat vectors.

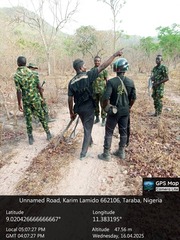

From Katsina to Niger, Kano and Zamfara, a chain of interlinked incidents reveals both the growing effectiveness of air power and intelligence-led ground operations, and the stubborn adaptability of armed criminal networks determined to survive under pressure.

At the core of the evolving campaign is the decisive Nigerian Air Force (NAF) offensive under Operation FANSAN YANMA in Katsina State. Sustained Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) enabled air assets to track the movement of about 50 motorcycles suspected to be ferrying armed bandits along a known infiltration corridor. When a large cluster converged in the Matazu axis, the convergence point was designated and struck with precision. Zagazola later obtained a video footage of the strike with dozens of bandits scattered and burnt beyond recognition.

The impact went beyond the immediate neutralisation of several bandits. By breaking a massed movement likely intended for an attack, redeployment or logistics transfer, the strike achieved a critical operational effect: fragmentation. In contemporary bandit warfare, where speed, numbers and surprise are force multipliers, denying criminals the ability to assemble is often as decisive as killing them outright.

Post-strike behaviour reinforced this assessment. Surviving elements scattered in disarray, disrupting coordination and degrading momentum. This pattern track, fix, strike, fragment increasingly defines the counter terrorism campaign in the North-West Operation FANSAN YANMA.

Yet the Katsina airstrike cannot be viewed in isolation. While bandit formations were being degraded from the air, armed groups continued probing vulnerabilities across the wider North-West corridor.

In Niger State’s Borgu axis, dozens of armed men on motorcycles attacked and set parts of a security outpost ablaze before fleeing. Although no casualties were recorded and no weapons lost, the incident carried symbolic weight. It illustrated the persistence of bandit and insurgent-linked elements in targeting state authority, particularly in remote, border-adjacent communities where response times are tested.

That same transnational dynamic was evident in the crash of a NAF drone on farmland in Kontagora. The drone, reportedly on an operational mission, pointed to the intensity and geographic spread of aerial surveillance and strike efforts. While no casualties were recorded, the incident illustrated the risks inherent in sustained high-tempo ISR operations across vast and rugged terrain.

On the ground, bandit violence continues to exact a human and economic toll. In Katsina’s Malumfashi axis, suspected bandits attacked Naino village, killing two residents and injuring six others. Joint security deployments, medical evacuation and blocking operations followed, but the incident reinforced a grim truth: even as air power constrains large-scale movements, smaller cells retain the ability to strike villages with lethal effect.

Similarly, in Katsina border communities near the Niger Republic, bandits rustled cattle and injured residents who attempted to resist them. Livestock theft remains central to the bandit economy, a source of funding, food and leverage over rural populations.

Further south in Kano State, attacks in Shanono and Tsanyawa LGAs revealed another layer of the conflict. In Farin-Fuwa village, bandits engaged responding forces in a gun battle that claimed the life of a soldier. In Tsanyawa, cattle rustlers struck and escaped before security teams arrived. These incidents show how bandit groups oscillate between direct confrontation and economic sabotage, depending on opportunity and resistance.

Zamfara State continues to illustrate the most complex end of the spectrum. In Bukuyyum LGA, armed bandits and elements of the outlawed YANSAKAI group carried out fatal attacks, including the killing of a civilian inside a mosque and the murder of local hunters along rural routes.

At the same time, swift intervention by security forces in another incident prevented the abduction of civilians, drawing attention to the difference timely intelligence and rapid response can make. Ongoing operations by the troops of Operation FANSAN YANMA in the Bukuyyum–Mada axis now focus on tracking fleeing elements, dominating forest corridors and recovering looted arms.

Taken together, these incidents reveal a theatre in transition rather than resolution. Bandit groups are increasingly constrained in their ability to move in large, coordinated formations, largely due to ISR-driven air operations. Yet they remain capable of opportunistic attacks, arson, targeted killings and cattle rustling, particularly in rural and border communities.

The response, correspondingly, is becoming more intelligence-centric. ISR now underpins both air interdiction and ground manoeuvre. Blocking operations, area domination and follow-on patrols increasingly complement strikes from the air, creating cumulative pressure that limits regrouping.

What is unfolding in the North-West is not a single decisive battle, but a campaign of attrition. Air power disrupts, dislocates and degrades. Ground actions deny escape, recover weapons and reassure communities.

Yet, the challenge remains far from over. Bandit networks are fluid, opportunistic and deeply embedded in difficult terrain. Sustaining pressure, maintaining ISR superiority and denying escape routes will be critical in preventing regrouping and retaliatory attacks.

The strategic lesson is clear: sustained dominance requires continuity. Tactical victories, no matter how precise, must be followed by relentless monitoring, cross-state coordination and disruption of the economic lifelines that sustain banditry.

As 2026 unfolds, early indicators suggest that when intelligence leads and force follows decisively, criminal networks pay a heavy price. The challenge ahead lies in sustaining this momentum long enough to convert battlefield success into lasting stability for communities across Katsina, Niger, Kano, Zamfara and the wider North-West region.

Zagazola Makama is a Counter Insurgency Expert and Security Analyst in the Lake Chad region.